Rubber, a versatile and ubiquitous material, plays a crucial role in modern life. From tires and footwear to medical devices and industrial applications, rubber’s utility is undeniable. However, the question of whether rubber constitutes hazardous waste is complex, encompassing environmental, health, and regulatory considerations. This blog explores the nature of rubber, its environmental impact, and the debates surrounding its classification as hazardous waste.

Understanding Rubber: Natural vs. Synthetic

Rubber can be broadly categorized into two types: natural rubber and synthetic rubber.

- Natural Rubber: Derived from the latex sap of rubber trees (Hevea brasiliensis), natural rubber is a renewable resource. It is prized for its elasticity, resilience, and resistance to abrasion and fatigue. Natural rubber is used in a wide range of products, including tires, medical supplies, and adhesives.

- Synthetic Rubber: Created through the polymerization of petroleum-based monomers, synthetic rubber encompasses various types such as styrene-butadiene rubber (SBR), nitrile rubber (NBR), and silicone rubber. These materials are tailored for specific properties like chemical resistance, temperature tolerance, and durability. Synthetic rubber is prevalent in automotive parts, industrial machinery, and consumer goods.

Rubber’s Environmental Footprint

The environmental impact of rubber spans its production, usage, and disposal phases. Understanding these impacts is key to evaluating its potential classification as hazardous waste.

Production Phase

- Natural Rubber: While natural rubber is renewable, its cultivation has significant ecological implications. Large-scale rubber plantations often lead to deforestation, loss of biodiversity, and soil degradation. The processing of natural rubber also involves chemicals and generates waste, contributing to pollution.

- Synthetic Rubber: The production of synthetic rubber is energy-intensive and relies on non-renewable petroleum resources. The extraction and refining of crude oil, followed by the polymerization process, emit greenhouse gases and pollutants. Additionally, synthetic rubber production consumes large quantities of water and generates hazardous by-products.

Usage Phase

Rubber products, especially tires, have a long lifespan and provide critical functions in transportation, healthcare, and industry. However, the wear and tear of rubber products can release microplastics and other contaminants into the environment. For example, tire wear particles contribute to air and water pollution, posing risks to human health and ecosystems.

Disposal Phase

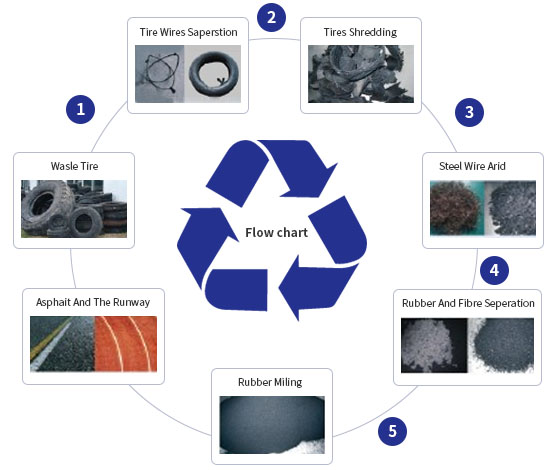

The disposal of rubber products presents significant challenges. Traditional disposal methods include landfilling, incineration, and recycling, each with its own environmental implications.

- Landfilling: Rubber waste in landfills is problematic due to its bulkiness, slow degradation rate, and potential to leach harmful chemicals into the soil and groundwater. Tires, in particular, can trap methane gas, causing landfill fires and explosions.

- Incineration: Burning rubber waste can generate energy but also releases toxic emissions such as dioxins, furans, and heavy metals. These pollutants can harm air quality and public health.

- Recycling: Recycling rubber, especially tires, can mitigate some environmental impacts. Ground rubber can be used in road construction, playground surfaces, and new rubber products. However, the recycling process itself can be energy-intensive and produce hazardous by-products.

Health and Environmental Risks

Rubber waste, particularly from tires, poses several health and environmental risks. These risks are crucial in determining whether rubber should be classified as hazardous waste.

Chemical Composition

Rubber products often contain additives such as plasticizers, stabilizers, and flame retardants to enhance performance. Some of these chemicals, like phthalates and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), are known to be toxic, carcinogenic, or endocrine-disrupting. When rubber products degrade or are incinerated, these chemicals can be released into the environment, posing risks to human health and wildlife.

Microplastics

As rubber products degrade, they generate microplastics—tiny particles less than 5 millimeters in size. These particles are pervasive in the environment, contaminating air, water, and soil. Microplastics can absorb and transport pollutants, entering the food chain and impacting marine and terrestrial life. The ingestion of microplastics by animals can lead to physical harm, reproductive issues, and the bioaccumulation of toxins.

Fire Hazards

Rubber, especially in the form of stockpiled tires, is highly flammable. Tire fires are difficult to extinguish and can burn for extended periods, releasing thick black smoke and a cocktail of toxic chemicals. These fires can have devastating effects on air quality, public health, and local ecosystems.

Regulatory Landscape

The classification of rubber as hazardous waste varies across jurisdictions, influenced by environmental policies, waste management practices, and scientific research.

International Regulations

Internationally, the Basel Convention regulates the transboundary movement of hazardous wastes. While rubber is not explicitly listed as hazardous under the convention, certain rubber waste containing hazardous chemicals may fall under its scope. The convention aims to prevent the illegal dumping of hazardous waste in developing countries and promotes environmentally sound waste management practices.

National Regulations

National regulations on rubber waste differ widely. For instance:

- United States: The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) does not classify rubber, including tires, as hazardous waste under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA). However, states can impose stricter regulations. For example, California classifies shredded tires as a hazardous waste unless properly managed.

- European Union: The European Waste Catalogue (EWC) categorizes waste based on its composition and potential hazards. While most rubber waste is not classified as hazardous, certain rubber-containing materials, such as those with high levels of hazardous additives, may be classified as hazardous.

- Japan: Japan has stringent regulations for waste management, including rubber waste. The country promotes recycling and has developed advanced technologies for rubber recycling, minimizing environmental impacts.

The Debate: Is Rubber a Hazardous Waste?

The debate over whether rubber should be classified as hazardous waste hinges on several factors:

Environmental Impact

Proponents of classifying rubber as hazardous waste argue that its environmental impact justifies stricter regulations. The release of toxic chemicals, the persistence of microplastics, and the risks of tire fires highlight the potential hazards of rubber waste. Classifying rubber as hazardous could incentivize better waste management practices, reduce pollution, and protect public health.

Economic and Practical Considerations

Opponents argue that classifying rubber as hazardous waste could impose significant economic and practical challenges. The costs of managing and disposing of hazardous waste are higher, which could burden industries and consumers. Additionally, the infrastructure for hazardous waste management may not be equipped to handle the large volumes of rubber waste, leading to potential inefficiencies and unintended consequences.

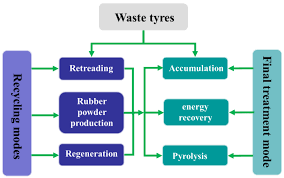

Advances in Recycling Technology

Advances in rubber recycling technology offer a middle ground. By improving recycling methods, the environmental impact of rubber waste can be mitigated without the need for hazardous waste classification. Innovations such as devulcanization, pyrolysis, and the use of recycled rubber in new products demonstrate the potential for sustainable rubber waste management.

Conclusion

The question of whether rubber constitutes hazardous waste is multifaceted, involving environmental, health, and regulatory dimensions. While rubber, particularly synthetic rubber, has significant environmental impacts and potential health risks, the classification of rubber as hazardous waste remains debated. Striking a balance between environmental protection and practical considerations is essential.

Enhanced recycling technologies, stricter regulations on hazardous additives, and international cooperation can help address the challenges of rubber waste. By fostering sustainable practices and innovation, society can mitigate the environmental impact of rubber while reaping its benefits.

In conclusion, rubber’s status as hazardous waste is not a black-and-white issue. It requires a nuanced approach that considers the material’s lifecycle, environmental footprint, and potential risks. By promoting responsible production, usage, and disposal, we can ensure that rubber remains a valuable resource without compromising environmental and public health.